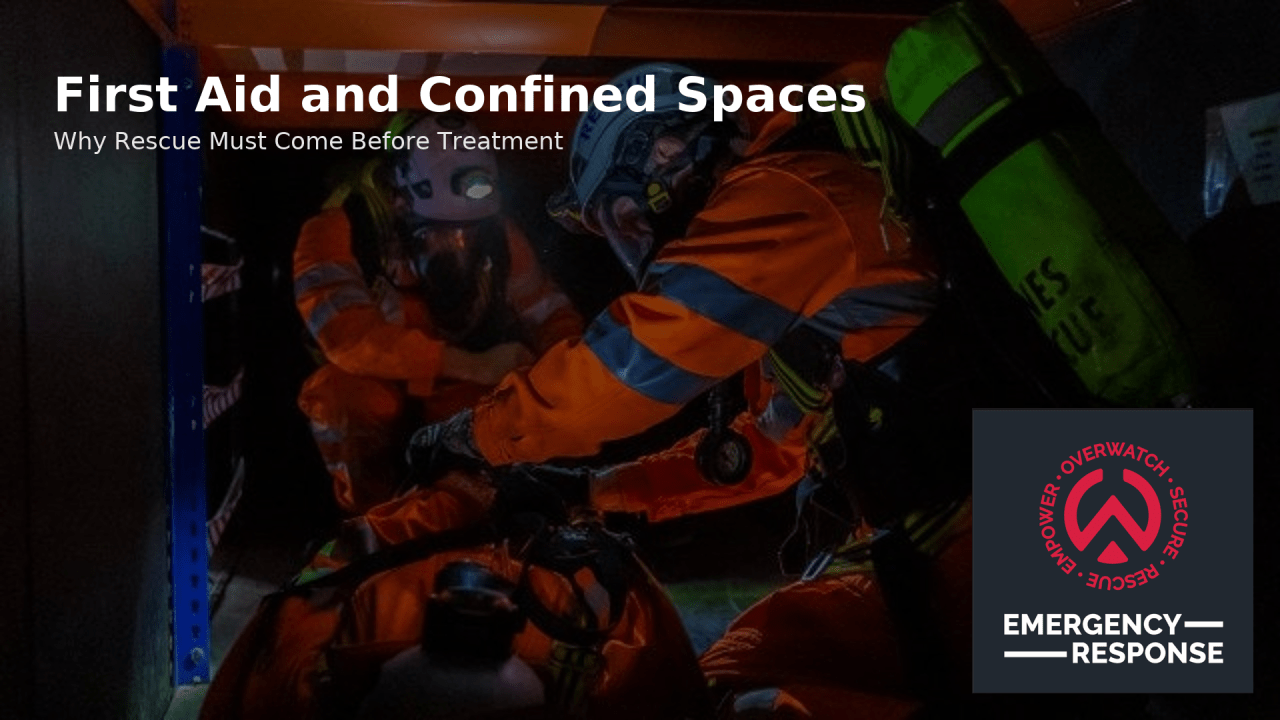

When people hear “first aid at work,” they picture a well-lit factory floor, a clean airway assessment, and a quick phone call to emergency services. Confined spaces are nothing like that.

Tanks, tunnels, silos, culverts, and sewers compound medical problems with unique environmental threats: toxic or oxygen-poor atmospheres, restricted access, entrapment, noise, poor visibility, and the ever-present risk of creating multiple casualties through attempted self-rescue or improvised entry.

This article takes a clear stance: first aid should not be performed inside a confined space unless it is delivered by a properly equipped and competent rescue team operating under a safe system of work.

For everyone else, the ethic is simple and uncompromising: rescue to a place of safety first; treat second.

The Four Gases Everyone Talks About—and Why They Matter

Most confined space monitoring regimes focus on four gases because they account for the majority of immediately dangerous atmospheres:

- Oxygen (O₂) – Too little and patients (and would-be rescuers) lose consciousness rapidly; too much and fire risk escalates. Oxygen concentration can change quickly and unpredictably.

- Hydrogen sulphide (H₂S) – A highly toxic gas that paralyzes the olfactory nerve; the “rotten egg smell” is not a reliable warning. Even short, high-dose exposures can cause sudden collapse.

- Carbon monoxide (CO) – Colourless, odourless, binds to haemoglobin far more readily than oxygen, starving tissues despite a “normal” respiratory effort and pink skin tone.

- Methane (CH₄) – Typically discussed for its explosivity and displacement of oxygen rather than inherent toxicity; any ignition source becomes a major threat.

Normal workplace first aid courses do not equip you to diagnose, mitigate, or safely treat gas-related injuries in a hazardous atmosphere. Recognising that someone is hypoxic or poisoned is not the same as safely entering, ventilating, monitoring, and extricating them.

Why Standard First Aid Training Falls Short in Confined Spaces

General first aid courses are designed for open, safe environments.

They assume:

- Accessible patient in breathable air,

- Stable scene without dynamic atmospheric risk,

- Rapid external help en route,

- Minimal PPE requirements.

Confined spaces violate all four assumptions. To treat safely inside the space, responders need far more than “first aid”:

- Atmospheric monitoring competence (pre-entry and continuous, with alarm interpretation and response).

- Ventilation strategies and an understanding of how airflow moves in that specific geometry.

- Permit-to-work literacy and lockout/tagout integration.

- Technical rescue capability (rigging, hauling, packaging, casualty handling in restricted layouts).

- Breathing apparatus (often SCBA) with training, fit testing, duration calculations, emergency procedures, and team stepping.

- Command, communication, and contingency planning (including non-entry rescue options and abort criteria).

Without these, attempting “treatment” inside the hazard zone is not first aid, it’s an uncontrolled rescue attempt that commonly ends in a second victim.

“Should We Ever Send Someone In for Medical Interventions?”

Only if all the following are true:

- There is a formal rescue plan (written, briefed, rehearsed) that includes medical interventions within the space.

- Trained, equipped rescue personnel are present (not just workers with a first aid card).

- Continuous monitoring is in place with competent interpretation and action thresholds.

- Appropriate RPE (usually SCBA) is available, serviceable, and used by personnel with current competence.

- A safe system of work (permit, isolations, LOTO, ventilation, attendant, communications, retrieval) is active.

- Abort criteria are clear and binding (gas alarms, comms failure, line tension anomalies, time-on-air limits, deteriorating conditions).

In other words, medical care inside the space is a rescue function, not a first aid function. If your team cannot satisfy the above, do not enter.

First Aid Is Exactly What It Says on the Tin: First, Not Final

First aid is initial care to preserve life, prevent deterioration, and promote recovery until more definitive help arrives. In confined spaces, that “initial care” begins with making the scene safe and initiating a rescue to fresh air. Once the casualty is out:

- Airway & Breathing: Prioritise airway positioning, suction if available, high-flow oxygen if trained and authorised, and ventilation support if indicated.

- Circulation & Haemorrhage: Control catastrophic bleeding immediately (pressure, haemostatic dressings, tourniquet when appropriate). Manage shock aggressively (warmth, minimal movement if spinal risk).

- Gas Exposure Considerations: Suspected CO or H₂S exposure? High-flow oxygen and rapid handover to advanced care. Do not delay evacuation for “on-scene” treatments you’re not equipped to deliver.

- Packaging & Handover: Patient packaging should facilitate rapid movement and ongoing monitoring; handover should include atmospheric readings, time in space, and PPE used.

Inside the space, any attempt to do these tasks without the capabilities listed earlier is unsafe.

The Safe Person Concept—Preached Exhaustively, Practised Relentlessly

The Safe Person Concept is non-negotiable:

- Your safety. You are no use as a second casualty.

- Your team’s safety. Don’t compromise a whole crew for a single improvised act.

- Then the casualty’s welfare. A living, breathing rescuer outside the space is the casualty’s best chance of survival.

If you feel panic rising, default to protocol:

- Stop. Breathe. Check alarms and time.

- Confirm comms with the attendant/top person.

- Re-verify the plan or initiate the emergency plan.

- Request the designated rescue team if not already on standby.

Panic makes bad physics worse. Gas doesn’t negotiate.

Self-Rescue and Co-Worker Rescue: The Multiplying Risk

Many fatalities occur when co-workers attempt spontaneous rescue. Common patterns:

- A worker collapses; a colleague rushes in unprotected and collapses; a third follows…

- A space is “quiet yesterday, so it’s probably fine,” and monitoring is skipped.

- The team relies on smell to detect H₂S or “feels normal” breathing to dismiss CO.

Break the chain: if you don’t have the equipment, competence, and plan to enter, don’t. Call the rescue team and manage the scene from safety.

So… Should First Aid Be Considered In a Confined Space?

Yes, by a trained, equipped confined space rescue team working to a rehearsed plan.

No, by general first aiders or co-workers without that capability.

For most workplaces, the correct model is:

- Plan for non-entry rescue first. Use retrieval systems (tripods, davits, winches) and continuous monitoring to avoid committing personnel.

- If entry rescue is foreseeable, it requires dedicated training, equipment, staffing, and governance. That’s a rescue programme, not a first aid add-on.

- First aid belongs at the point of safety after extraction—where air is breathable, lighting is workable, and risk is manageable.

Practical Framework for Employers and Teams

Before work begins

- Hazard identification & risk assessment specific to the space and task.

- Permit-to-work with isolation/LOTO and ventilation plan.

- Rescue plan proportionate to the risk (non-entry preferred; entry only with full capability).

- Competence assurance: entrants, attendants, supervisors, and (if applicable) rescue technicians.

- Equipment readiness: calibrated gas monitors, retrieval systems, comms, SCBA, medical kit appropriate to foreseeable injuries.

During operations

- Continuous monitoring with documented readings and alarm responses.

- Strict role separation: attendant does not enter; entrants do not become rescuers ad hoc.

- Time-on-air and reliefs controlled where BA is in use.

- Abort early if alarms, comms failures, or conditions deteriorate.

If an incident occurs

- Activate the rescue plan—not improvisation.

- Prioritise extraction to safety.

- Deliver first aid outside the hazard, focusing on airway, breathing (oxygen where approved), and catastrophic haemorrhage.

- Clinical handover includes atmospheric data and exposure timelines.

A Short Word on Kit Creep

It’s tempting to “upgrade” first aid kits with oxygen, suction, airway adjuncts, and haemostatics. Equipment without competence and context can become a liability. Match kit to your plan and training, not the other way around.

Bottom Line

- First aid inside a confined space is a rescue task, not a basic skill.

- Rescue first, treat second is the doctrine that prevents multiple fatalities.

- Safe Person Concept isn’t a slogan—it’s the rule of survival: you, your team, then the casualty.

If your current arrangements imply that a standard first aider will “sort things out” inside the space, you don’t have a first aid problem—you have a rescue planning problem. Fix the plan, build the capability, rehearse the response, and keep your people alive.

If your team works in confined spaces, don’t leave emergency response to chance. Overwatch Response provides professional standby rescue teams and on-site paramedic support for high-risk operations.

- Confined space standby rescue

- Working at height rescue

- Industrial and chemical environments

- Onsite paramedics and advanced medical care

- Professional technical rescuers from emergency services backgrounds

- Full rescue planning, compliance and risk reduction

Protect your people. Protect your business. Don’t let your team become the rescue plan.

Article by Mark Hyland MA

Founder & CEO | Emergency Response & Rescue Standby Services | Safety Training & Risk Assessments